The value of this article is in describing how Neoliberalism became a self fulfilling viscous cycle. How the market forces "Winners" and "Losers" to self identify. Why people with a little bit of money think they are geniuses.

Neoliberalism – the ideology at the root of all our problems

Financial meltdown, environmental disaster and even the rise of Donald Trump – neoliberalism has played its part in them all. Why has the left failed to come up with an alternative?

George MonbiotFri 15 Apr 2016 07.00 EDT

Last modified on Wed 29 Nov 2017 05.47 EST

Imagine if the people of the Soviet Union had never heard of communism. The ideology that dominates our lives has, for most of us, no name. Mention it in conversation and you’ll be rewarded with a shrug. Even if your listeners have heard the term before, they will struggle to define it. Neoliberalism: do you know what it is?

Its anonymity is both a symptom and cause of its power. It has played a major role in a remarkable variety of crises: the financial meltdown of 2007‑8, the offshoring of wealth and power, of which the Panama Papers offer us merely a glimpse, the slow collapse of public health and education, resurgent child poverty, the epidemic of loneliness, the collapse of ecosystems, the rise of Donald Trump. But we respond to these crises as if they emerge in isolation, apparently unaware that they have all been either catalysed or exacerbated by the same coherent philosophy; a philosophy that has – or had – a name. What greater power can there be than to operate namelessly?

Inequality is recast as virtuous. The market ensures that everyone gets what they deserve.

So pervasive has neoliberalism become that we seldom even recognise it as an ideology. We appear to accept the proposition that this utopian, millenarian faith describes a neutral force; a kind of biological law, like Darwin’s theory of evolution. But the philosophy arose as a conscious attempt to reshape human life and shift the locus of power.

Neoliberalism sees competition as the defining characteristic of human relations. It redefines citizens as consumers, whose democratic choices are best exercised by buying and selling, a process that rewards merit and punishes inefficiency. It maintains that “the market” delivers benefits that could never be achieved by planning.

Sign up for Bookmarks: discover new books in our weekly email

Read more

Attempts to limit competition are treated as inimical to liberty. Tax and regulation should be minimised, public services should be privatised. The organisation of labour and collective bargaining by trade unions are portrayed as market distortions that impede the formation of a natural hierarchy of winners and losers. Inequality is recast as virtuous: a reward for utility and a generator of wealth, which trickles down to enrich everyone. Efforts to create a more equal society are both counterproductive and morally corrosive. The market ensures that everyone gets what they deserve.

We internalise and reproduce its creeds. The rich persuade themselves that they acquired their wealth through merit, ignoring the advantages – such as education, inheritance and class – that may have helped to secure it. The poor begin to blame themselves for their failures, even when they can do little to change their circumstances.

Never mind structural unemployment: if you don’t have a job it’s because you are unenterprising. Never mind the impossible costs of housing: if your credit card is maxed out, you’re feckless and improvident. Never mind that your children no longer have a school playing field: if they get fat, it’s your fault. In a world governed by competition, those who fall behind become defined and self-defined as losers.

Neoliberalism has brought out the worst in us

Paul Verhaeghe

Read more

Among the results, as Paul Verhaeghe documents in his book What About Me? are epidemics of self-harm, eating disorders, depression, loneliness, performance anxiety and social phobia. Perhaps it’s unsurprising that Britain, in which neoliberal ideology has been most rigorously applied, is the loneliness capital of Europe. We are all neoliberals now.

***

The term neoliberalism was coined at a meeting in Paris in 1938. Among the delegates were two men who came to define the ideology, Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich Hayek. Both exiles from Austria, they saw social democracy, exemplified by Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal and the gradual development of Britain’s welfare state, as manifestations of a collectivism that occupied the same spectrum as nazism and communism.

In The Road to Serfdom, published in 1944, Hayek argued that government planning, by crushing individualism, would lead inexorably to totalitarian control. Like Mises’s book Bureaucracy, The Road to Serfdom was widely read. It came to the attention of some very wealthy people, who saw in the philosophy an opportunity to free themselves from regulation and tax. When, in 1947, Hayek founded the first organisation that would spread the doctrine of neoliberalism – the Mont Pelerin Society – it was supported financially by millionaires and their foundations.

With their help, he began to create what Daniel Stedman Jones describes in Masters of the Universe as “a kind of neoliberal international”: a transatlantic network of academics, businessmen, journalists and activists. The movement’s rich backers funded a series of thinktanks which would refine and promote the ideology. Among them were the American Enterprise Institute, the Heritage Foundation, the Cato Institute, the Institute of Economic Affairs, the Centre for Policy Studies and the Adam Smith Institute. They also financed academic positions and departments, particularly at the universities of Chicago and Virginia.

As it evolved, neoliberalism became more strident. Hayek’s view that governments should regulate competition to prevent monopolies from forming gave way – among American apostles such as Milton Friedman – to the belief that monopoly power could be seen as a reward for efficiency.

Something else happened during this transition: the movement lost its name. In 1951, Friedman was happy to describe himself as a neoliberal. But soon after that, the term began to disappear. Stranger still, even as the ideology became crisper and the movement more coherent, the lost name was not replaced by any common alternative.

At first, despite its lavish funding, neoliberalism remained at the margins. The postwar consensus was almost universal: John Maynard Keynes’s economic prescriptions were widely applied, full employment and the relief of poverty were common goals in the US and much of western Europe, top rates of tax were high and governments sought social outcomes without embarrassment, developing new public services and safety nets.

But in the 1970s, when Keynesian policies began to fall apart and economic crises struck on both sides of the Atlantic, neoliberal ideas began to enter the mainstream. As Friedman remarked, “when the time came that you had to change ... there was an alternative ready there to be picked up”. With the help of sympathetic journalists and political advisers, elements of neoliberalism, especially its prescriptions for monetary policy, were adopted by Jimmy Carter’s administration in the US and Jim Callaghan’s government in Britain.

It may seem strange that a doctrine promising choice should have been promoted with the slogan 'there is no alternative'

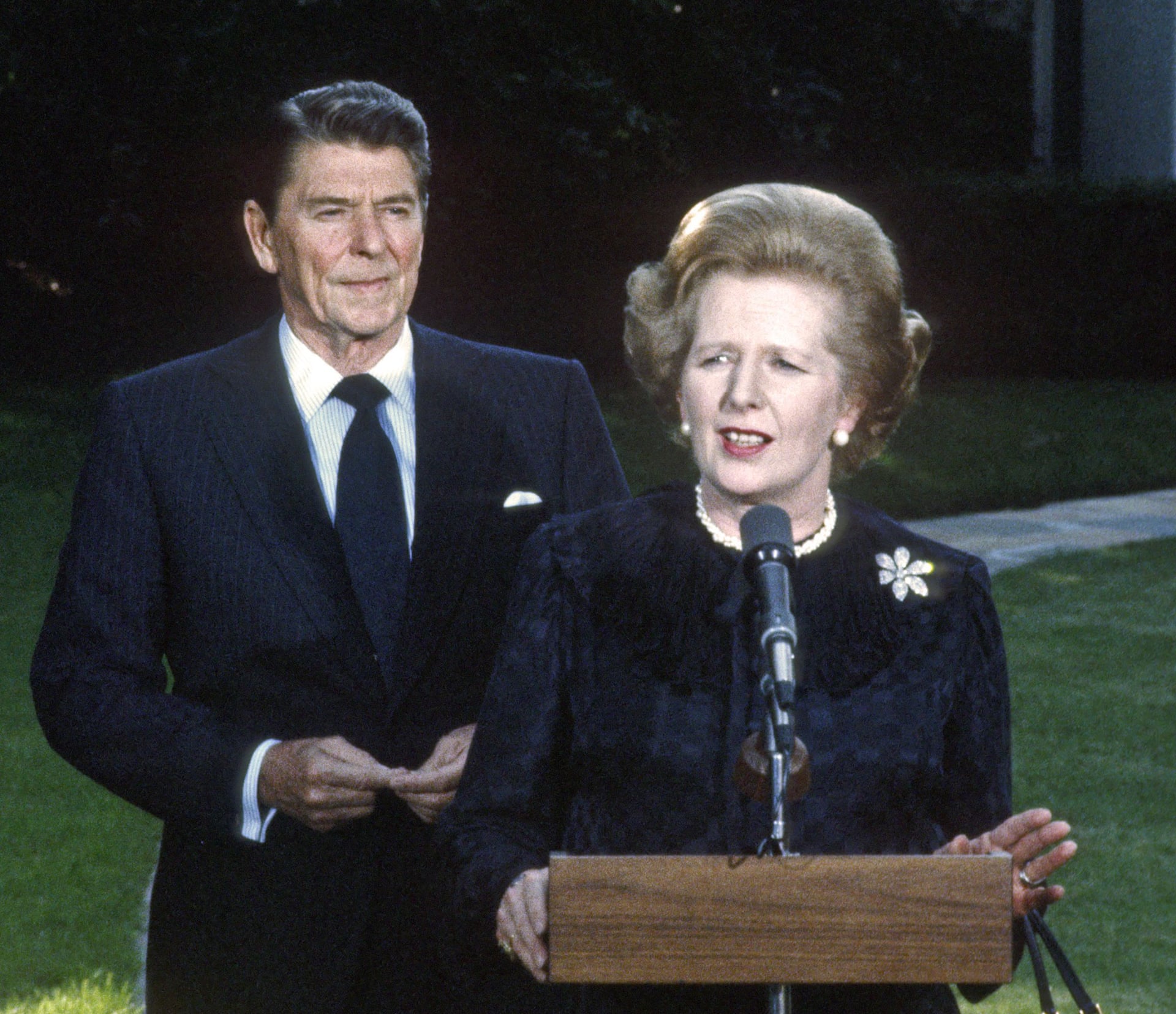

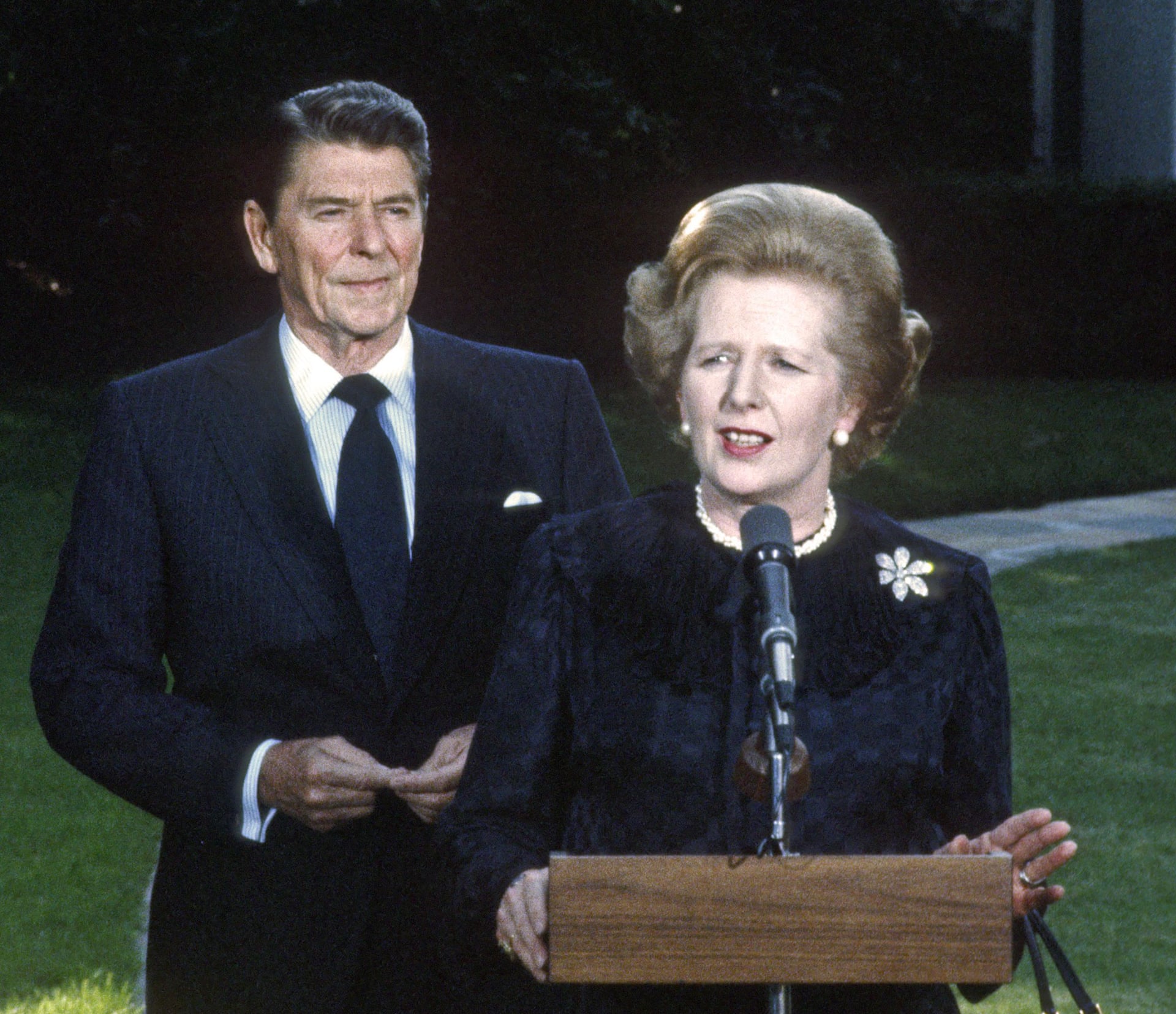

After Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan took power, the rest of the package soon followed: massive tax cuts for the rich, the crushing of trade unions, deregulation, privatisation, outsourcing and competition in public services. Through the IMF, the World Bank, the Maastricht treaty and the World Trade Organisation, neoliberal policies were imposed – often without democratic consent – on much of the world. Most remarkable was its adoption among parties that once belonged to the left: Labour and the Democrats, for example. As Stedman Jones notes, “it is hard to think of another utopia to have been as fully realised.”

***

It may seem strange that a doctrine promising choice and freedom should have been promoted with the slogan “there is no alternative”. But, as Hayek remarked on a visit to Pinochet’s Chile – one of the first nations in which the programme was comprehensively applied – “my personal preference leans toward a liberal dictatorship rather than toward a democratic government devoid of liberalism”. The freedom that neoliberalism offers, which sounds so beguiling when expressed in general terms, turns out to mean freedom for the pike, not for the minnows.

Freedom from trade unions and collective bargaining means the freedom to suppress wages. Freedom from regulation means the freedom to poison rivers, endanger workers, charge iniquitous rates of interest and design exotic financial instruments. Freedom from tax means freedom from the distribution of wealth that lifts people out of poverty.

Naomi Klein documented that neoliberals advocated the use of crises to impose unpopular policies while people were distracted. Photograph: Anya Chibis for the Guardian

As Naomi Klein documents in The Shock Doctrine, neoliberal theorists advocated the use of crises to impose unpopular policies while people were distracted: for example, in the aftermath of Pinochet’s coup, the Iraq war and Hurricane Katrina, which Friedman described as “an opportunity to radically reform the educational system” in New Orleans.

Where neoliberal policies cannot be imposed domestically, they are imposed internationally, through trade treaties incorporating “investor-state dispute settlement”: offshore tribunals in which corporations can press for the removal of social and environmental protections. When parliaments have voted to restrict sales of cigarettes, protect water supplies from mining companies, freeze energy bills or prevent pharmaceutical firms from ripping off the state, corporations have sued, often successfully. Democracy is reduced to theatre.

Neoliberalism was not conceived as a self-serving racket, but it rapidly became one

Another paradox of neoliberalism is that universal competition relies upon universal quantification and comparison. The result is that workers, job-seekers and public services of every kind are subject to a pettifogging, stifling regime of assessment and monitoring, designed to identify the winners and punish the losers. The doctrine that Von Mises proposed would free us from the bureaucratic nightmare of central planning has instead created one.

Neoliberalism was not conceived as a self-serving racket, but it rapidly became one. Economic growth has been markedly slower in the neoliberal era (since 1980 in Britain and the US) than it was in the preceding decades; but not for the very rich. Inequality in the distribution of both income and wealth, after 60 years of decline, rose rapidly in this era, due to the smashing of trade unions, tax reductions, rising rents, privatisation and deregulation.

The privatisation or marketisation of public services such as energy, water, trains, health, education, roads and prisons has enabled corporations to set up tollbooths in front of essential assets and charge rent, either to citizens or to government, for their use. Rent is another term for unearned income. When you pay an inflated price for a train ticket, only part of the fare compensates the operators for the money they spend on fuel, wages, rolling stock and other outlays. The rest reflects the fact that they have you over a barrel.

In Mexico, Carlos Slim was granted control of almost all phone services and soon became the world’s richest man. Photograph: Henry Romero/Reuters

Those who own and run the UK’s privatised or semi-privatised services make stupendous fortunes by investing little and charging much. In Russia and India, oligarchs acquired state assets through firesales. In Mexico, Carlos Slim was granted control of almost all landline and mobile phone services and soon became the world’s richest man.

Financialisation, as Andrew Sayer notes in Why We Can’t Afford the Rich, has had a similar impact. “Like rent,” he argues, “interest is ... unearned income that accrues without any effort”. As the poor become poorer and the rich become richer, the rich acquire increasing control over another crucial asset: money. Interest payments, overwhelmingly, are a transfer of money from the poor to the rich. As property prices and the withdrawal of state funding load people with debt (think of the switch from student grants to student loans), the banks and their executives clean up.

Sayer argues that the past four decades have been characterised by a transfer of wealth not only from the poor to the rich, but within the ranks of the wealthy: from those who make their money by producing new goods or services to those who make their money by controlling existing assets and harvesting rent, interest or capital gains. Earned income has been supplanted by unearned income.

Neoliberal policies are everywhere beset by market failures. Not only are the banks too big to fail, but so are the corporations now charged with delivering public services. As Tony Judt pointed out in Ill Fares the Land, Hayek forgot that vital national services cannot be allowed to collapse, which means that competition cannot run its course. Business takes the profits, the state keeps the risk.

The greater the failure, the more extreme the ideology becomes. Governments use neoliberal crises as both excuse and opportunity to cut taxes, privatise remaining public services, rip holes in the social safety net, deregulate corporations and re-regulate citizens. The self-hating state now sinks its teeth into every organ of the public sector.

Perhaps the most dangerous impact of neoliberalism is not the economic crises it has caused, but the political crisis. As the domain of the state is reduced, our ability to change the course of our lives through voting also contracts. Instead, neoliberal theory asserts, people can exercise choice through spending. But some have more to spend than others: in the great consumer or shareholder democracy, votes are not equally distributed. The result is a disempowerment of the poor and middle. As parties of the right and former left adopt similar neoliberal policies, disempowerment turns to disenfranchisement. Large numbers of people have been shed from politics.

Chris Hedges remarks that “fascist movements build their base not from the politically active but the politically inactive, the ‘losers’ who feel, often correctly, they have no voice or role to play in the political establishment”. When political debate no longer speaks to us, people become responsive instead to slogans, symbols and sensation. To the admirers of Trump, for example, facts and arguments appear irrelevant.

Judt explained that when the thick mesh of interactions between people and the state has been reduced to nothing but authority and obedience, the only remaining force that binds us is state power. The totalitarianism Hayek feared is more likely to emerge when governments, having lost the moral authority that arises from the delivery of public services, are reduced to “cajoling, threatening and ultimately coercing people to obey them”.

***

Like communism, neoliberalism is the God that failed. But the zombie doctrine staggers on, and one of the reasons is its anonymity. Or rather, a cluster of anonymities.

The invisible doctrine of the invisible hand is promoted by invisible backers. Slowly, very slowly, we have begun to discover the names of a few of them. We find that the Institute of Economic Affairs, which has argued forcefully in the media against the further regulation of the tobacco industry, has been secretly funded by British American Tobacco since 1963. We discover that Charles and David Koch, two of the richest men in the world, founded the institute that set up the Tea Party movement. We find that Charles Koch, in establishing one of his thinktanks, noted that “in order to avoid undesirable criticism, how the organisation is controlled and directed should not be widely advertised”.

The nouveau riche were once disparaged by those who had inherited their money. Today, the relationship has been reversed

The words used by neoliberalism often conceal more than they elucidate. “The market” sounds like a natural system that might bear upon us equally, like gravity or atmospheric pressure. But it is fraught with power relations. What “the market wants” tends to mean what corporations and their bosses want. “Investment”, as Sayer notes, means two quite different things. One is the funding of productive and socially useful activities, the other is the purchase of existing assets to milk them for rent, interest, dividends and capital gains. Using the same word for different activities “camouflages the sources of wealth”, leading us to confuse wealth extraction with wealth creation.

A century ago, the nouveau riche were disparaged by those who had inherited their money. Entrepreneurs sought social acceptance by passing themselves off as rentiers. Today, the relationship has been reversed: the rentiers and inheritors style themselves entre preneurs. They claim to have earned their unearned income.

These anonymities and confusions mesh with the namelessness and placelessness of modern capitalism: the franchise model which ensures that workers do not know for whom they toil; the companies registered through a network of offshore secrecy regimes so complex that even the police cannot discover the beneficial owners; the tax arrangements that bamboozle governments; the financial products no one understands.

The anonymity of neoliberalism is fiercely guarded. Those who are influenced by Hayek, Mises and Friedman tend to reject the term, maintaining – with some justice – that it is used today only pejoratively. But they offer us no substitute. Some describe themselves as classical liberals or libertarians, but these descriptions are both misleading and curiously self-effacing, as they suggest that there is nothing novel about The Road to Serfdom, Bureaucracy or Friedman’s classic work, Capitalism and Freedom.

***

For all that, there is something admirable about the neoliberal project, at least in its early stages. It was a distinctive, innovative philosophy promoted by a coherent network of thinkers and activists with a clear plan of action. It was patient and persistent. The Road to Serfdom became the path to power.

Neoliberalism, Locke and the Green party

Read more

Neoliberalism’s triumph also reflects the failure of the left. When laissez-faire economics led to catastrophe in 1929, Keynes devised a comprehensive economic theory to replace it. When Keynesian demand management hit the buffers in the 70s, there was an alternative ready. But when neoliberalism fell apart in 2008 there was ... nothing. This is why the zombie walks. The left and centre have produced no new general framework of economic thought for 80 years.

Every invocation of Lord Keynes is an admission of failure. To propose Keynesian solutions to the crises of the 21st century is to ignore three obvious problems. It is hard to mobilise people around old ideas; the flaws exposed in the 70s have not gone away; and, most importantly, they have nothing to say about our gravest predicament: the environmental crisis. Keynesianism works by stimulating consumer demand to promote economic growth. Consumer demand and economic growth are the motors of environmental destruction.

What the history of both Keynesianism and neoliberalism show is that it’s not enough to oppose a broken system. A coherent alternative has to be proposed. For Labour, the Democrats and the wider left, the central task should be to develop an economic Apollo programme, a conscious attempt to design a new system, tailored to the demands of the 21st century.